2019-2020-2021 Surveys

One of the findings of the recently-released demographic survey of Jewish Americans by the Pew Research Center is that the intermarriage rate among Jews has remained at a consistent rate; about 56% of respondents who are married report that their spouse is not Jewish.

There is also the American Community Survey (ACS) which has been asking respondents whether people got married in the previous 12 months. The ACS was to find out how people would mix. Some people marry across national-origin lines within panethnic groups (e.g., Mexicans marrying Puerto Ricans) but next to the race/ethnic marriage it becomes even more complex when a mixture of religious culture is involved.

Constant flux in Jewish communities

From the recent Pew Research Center survey, we get to see that the American Jewish population, like other religious groups, is in constant flux. Some people who were raised as Jews have left the religion, while some who were raised outside the faith now identify with it. Many others have switched denominations within Judaism – a trend that has seen the Reform movement grow modestly and Conservative Judaism experience a net loss.

The two branches of Judaism that long predominated in the U.S. have less of a hold on young Jews than on their elders. Roughly four-in-ten Jewish adults under 30 identify with either Reform (29%) or Conservative Judaism (8%), compared with seven-in-ten Jews ages 65 and older.

In Europe and North-America because of a rising anti-semitism we see that a lot of Jews and Jeshuaists prefer to stay in the shadow and are not eager anymore to let strangers in their circles. For the States of America, there is also evidence that the U.S. Jewish population is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. Overall, 92% of Jewish adults identify as White (non-Hispanic), and 8% identify with all other categories combined. But among Jews ages 18 to 29, that figure rises to 15%. Already, 17% of U.S. Jews surveyed live in households in which at least one child or adult is Black, Hispanic, Asian, some other (non-White) race or ethnicity, or multiracial.

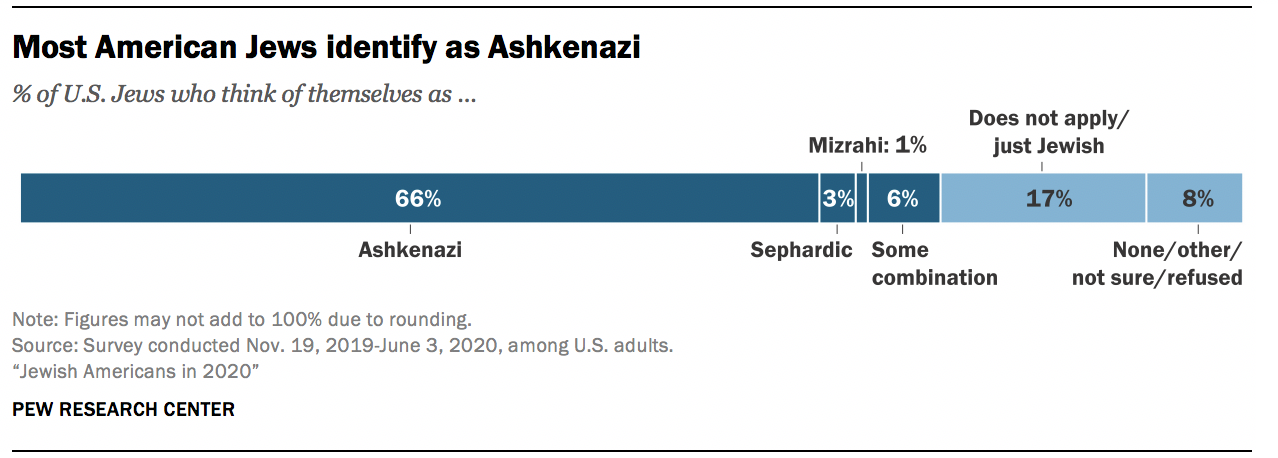

The survey also asked whether Jews think of themselves as Ashkenazi (following the Jewish customs of Central and Eastern Europe), Sephardic (following the Jewish customs of their ancestors who were expelled from Spain and Portugal), Mizrahi (or Oriental Jews, following the Jewish customs of North Africa and the Middle East) or something else. Fully two-thirds of Jewish Americans consider themselves Ashkenazi, while relatively few consider themselves to be Sephardic (3%) or Mizrahi (1%). An additional 6% say they are some combination of these or other categories.

Despite the fact that most American Jews identify as following Jewish customs from Europe, nine-in-ten were born in the United States (90%), including 21% who are the adult children of at least one immigrant and 68% whose families have been in the U.S. for three generations or longer. One-third of Jewish adults (32%) are first- or second-generation immigrants, including 20% who were born in Europe or had a parent born in Europe and 4% who are first- or second-generation immigrants from the Middle East-North Africa region (including Israel)

Equality and gender inequality

In most of the Jewish groups children learn that like we all are equal, having made in the image of the One God, there should be no difference between eachother, there being gender equality, secularism, brotherhood, etc. . Moral books are full of such teachings, but in real life it looks totally different, having several groups where the women have a secondary or even tertiary role to play.

Be it in the ‘modern’ America, in Europe or in Israel, there can be found a lot of gender disparity in Judaism as well as in Jeshuaism. Also in those regions, people are not so keen to find some of their family members mixing with others.

The attitude to other Jews often is also related to their stance to Israel and Zionism.

On average, the Orthodox are the most traditionally observant and emotionally attached to Israel; they tend to be politically conservative, with large families, very low rates of religious intermarriage and a young median age (35 years). Several followers of Jeshua (or Jeshuaists) because of having not many around them, go to an orthodox synagogue, where they seem to fit in as a classic Jehudi or an “Orthodox Jew” and where they do not tell about their faith in Jeshua. Most often they do not come into the public as followers of Jeshua. In most cases, those believers in Jeshua the Messiah do not go to other American Messianic groups, because the majority of them are trinitarians, and as such an abomination in the eyes of God.

Conservative and Reform Jews tend to be less religiously observant in traditional ways, like keeping kosher and regularly attending religious services, but many in these groups participate in Jewish cultural activities, and most are at least somewhat attached to Israel. Demographically, they have high levels of education, small families, higher rates of intermarriage than the Orthodox and an older age profile (median age of 62 for Conservative, 53 for Reform).

There is a fair amount of overlap – though it is far from complete – between the 32% of Jewish adults who do not consider themselves members of any branch or denomination of American Judaism and the 27% who are categorized as “Jews of no religion.”

Those who describe their religion as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular but who have a Jewish parent or were raised Jewish and say that aside from religion they consider themselves Jewish in some way – such as ethnically, culturally or because of their family background – are also fully included in the Jewish population throughout the Pew report. Survey researchers call them Jews of “no religion” because they do not identify with Judaism or any other religion. But what can be seen in all of them, living in the States, Europe or Israel, is that in some way they prefer to stay in their own circles, not mixing much with other Jewish groups and certainly not with goyim.

Halakha or more the importance of belonging

While there are some signs of religious divergence and political polarisation we can find large areas of consensus. All over Europe and North-America we can see that those Jews in a certain way feel connected with each other as Bnei Yisroel or People of God. More than eight-in-ten U.S. Jews say that they feel at least some sense of belonging to the Jewish people, and three-quarters say that “being Jewish” is either very or somewhat important to them.

Remarkable it might be that in the U.S.A. far fewer consider eating traditional Jewish foods (20%) and observing Jewish law (15%) to be essential elements of what being Jewish means to them, personally. It seems that fewer American Jews find themselves restricted by the “wire” around the town than their counterparts in Europe. The observance of halakha (Hebrew: “the Way”) – Jewish law – is particularly important to Orthodox Jews, 83% of whom deem it essential.

Views on halakha are just one of many stark differences in beliefs and behaviours between Orthodox Jews and Jewish Americans who identify with other branches of Judaism (or with no particular branch) that are evident in the survey, and that may affect how these groups perceive each other. For example, about half of Orthodox Jews in the U.S. say they have “not much” (23%) or “nothing at all” (26%) in common with Jews in the Reform movement; just 9% feel they have “a lot” in common with Reform Jews. In fact, there is little difference in attitude among Jews towards other denominations in Judaism compared to the attitude of Christians from one denomination towards another.

Reform Jews generally reciprocate those feelings: Six-in-ten say they have not much (39%) or nothing at all (21%) in common with the Orthodox, while 30% of Reform Jews say they have some things in common, and 9% say they have a lot in common with Orthodox Jews.

In fact, both Conservative and Reform Jews are more likely to say they have “a lot” or “some” in common with Jews in Israel (77% and 61%, respectively) than to say they have commonalities with Orthodox Jews in the United States. And Orthodox Jews are far more likely to say they have “a lot” or “some” in common with Israeli Jews (91%) than to say the same about their Conservative and Reform counterparts in the U.S..

Intermarriage and child-rearing

Both in America as in Europe, many Jews and Jeshuaists are not so happy in case someone would go to synagogues of another denomination or would marry someone from another group.

Decades ago it was just not done to marry a Jew from another branch and it was ‘from the devil’ to marry a goy or non-Jew.

Among Jewish respondents for the American survey who got married in the past decade, six-in-ten say they have a non-Jewish spouse. Among American Jews who got married between 2000 and 2009, fewer (45%) are intermarried, as are about four-in-ten who got married in the 1990s (37%) or 1980s (42%). By contrast, just 18% of Jews who got married before 1980 have a non-Jewish spouse.

In the States like in Europe one can say that intermarriage is almost nonexistent in the Orthodox Jewish community. Also in the Conservative Jeshuaist groups, a marriage with a non-trinitarian would be considered as impossible. The more contemporary Jeshuaists are aware that their community is just too small to find an appropriate spouse. Therefore to find a suitable partner it is often a serious debate what sort of person from another religion may be chosen.

In the States like in Europe one can say that intermarriage is almost nonexistent in the Orthodox Jewish community. Also in the Conservative Jeshuaist groups, a marriage with a non-trinitarian would be considered as impossible. The more contemporary Jeshuaists are aware that their community is just too small to find an appropriate spouse. Therefore to find a suitable partner it is often a serious debate what sort of person from another religion may be chosen.

In the current Pew survey, just 2% of married Orthodox Jews in the U.S.A. say their spouse is not Jewish. By contrast, among married Jews outside the Orthodox community, about half (47%) say their marriage partner (always from the other sex: husband or wife) is not Jewish. And among non-Orthodox Jews who got married in the last decade, 72% say they are intermarried – virtually the same as the 2013 survey found in the decade prior to that study. The study does not say anything about marriages between the same sex. Though it is known that there are also some Jews who have taken a companion or better half of the same gender.

In certain Jewish communities, the matchmaker is still used to bring people together. for the parents this seems the best and safest way to find a suitable partner for their children. The matchmaker takes care that people shall not marry for unreal and imaginary concepts because then they are bound to be disappointed. The choice of whom to marry to whom is something that has to be secure and safe, build on a good base and becomes framed in covenantal terms:

Will this marriage maintain the family’s distinct religious identity, or instead lead it to blend into the surrounding culture? This question plays a tense and tragic role within the first families and drives the central drama of Toledot. {Toledot 5778: A Family of Covenant}

In certain cultures, it might be that intermarriage delivers a surplus to both families. It is both the condition and mechanism for assimilation.

From the start to the finish, the Hebrew Bible is concerned with intermarriage, but not from any sense of national superiority. Indeed, the Torah emphasizes that Israel is “the least of the peoples” (Deut. 7:7). It is all about the Covenant—will this little people maintain its distinctive religious culture, exclusively worshipping the God of their ancestors, or will they merge with the larger population that surrounds them, relinquishing their distinctive faith and identity? {Toledot 5778: A Family of Covenant}

The majority of Jews and Jeshuaists are convinced they have a special relationship with the Bore. They consider themselves as Bnei Yisroel who have to keep themselves pure, as a people set apart for God. Parents know that they can’t predict or control how their kids ultimately turn out, and siblings with the same genetics and raised the same way could turn out completely different. For some parents, it is a given fact that when the son or daughter would go with a heathen, this would mean that the family breaks with that son or daughter. They go so far as to say:

A mother who lives with a goy is not your mother. You should never call her or write her or even recognize that she’s alive. {Rav Avigdor Miller on When To Ignore Your Parents – Parshas Bereishis 4 – The Marriage Bond}

For many Jewish teachers, it is clear that when a person runs away with a gentile person, that runner, goes away from God and has no part to play anymore in the People of God. A man has to cling to a good and respectful wife. For many, there is one important rule for marriage partners:

If a Jew chalilah marries a gentile

We react is as if the person doesn’t exist; we have nothing to do with that person at all. If you pass him on the street, he’s a zombie, he’s a ghost, he’s a dead man. You don’t see him. And you don’t see his mother and his father either. If his mother and father maintain relations with him; if he takes his shikseh and visits his parents and they let him in the house then you forget about his parents too. You don’t even know them. Anybody who harbors these people, anybody who has personal relations with them, you have nothing to do with them. That always was the system of the Jews and it should remain the system forever. {Rav Avigdor Miller on When To Ignore Your Parents}

though we must be aware of the dangers:

Where love and compatibility are not the main criteria in choosing a life partner, political and religious leaders have, historically, tried to intervene in people’s love lives, telling them whom they can and cannot marry. {Mixed marriage – Thoughts at the end of 2020}

From those who have married with someone from ‘outside’ their community we hear that has its disadvantages but also some surpluses. One can, in such case, not ignore the cultural difference, which can bring some discussions around the table, but it is also the “spice of life”

And, biologically speaking, variety makes for stronger communities, such as plant diversity in ecosystems. {Mixed marriage – Thoughts at the end of 2020}

But there is the ‘grand fear’ that the intermarriage partners would not raise their children in ‘the True Faith’.

Passing along Jewish identity

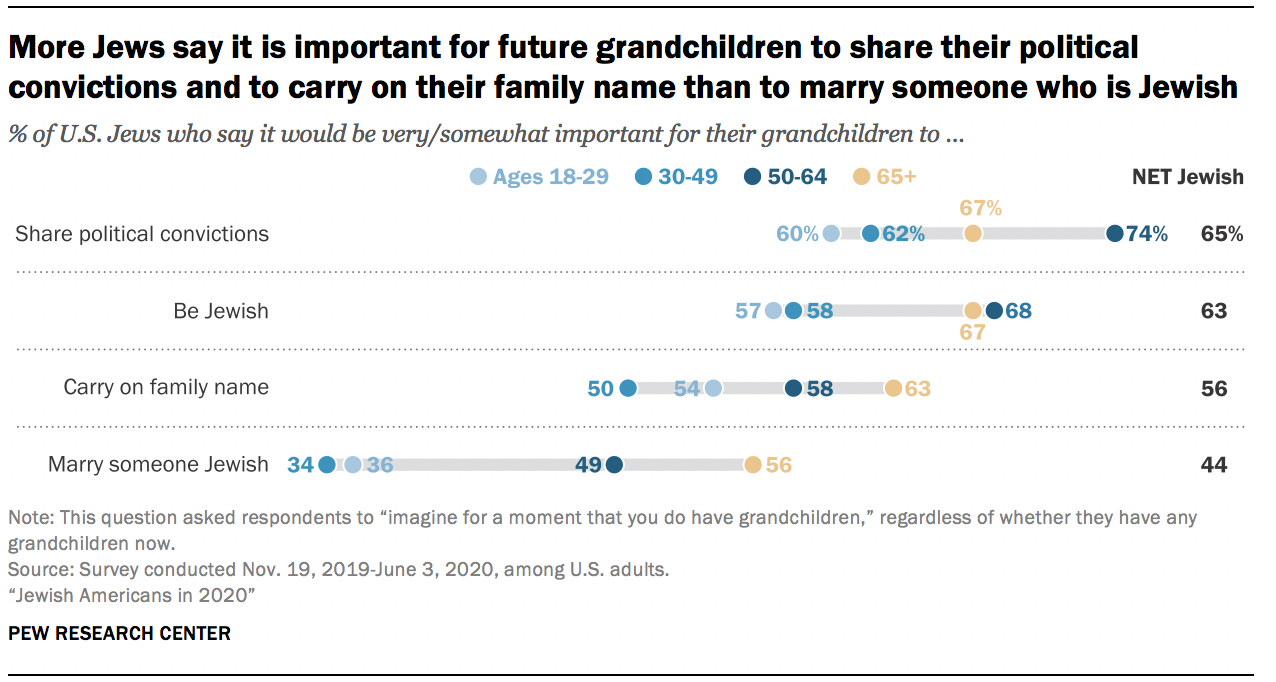

The 2020 Pew survey included a new question aimed at helping to assess the importance to Jewish Americans of passing along their Jewish identity. Asked to imagine a time in the future when they have grandchildren of their own (if they do not currently have any), roughly six-in-ten U.S. Jews say it would be very important (34%) or somewhat important (28%) for their grandchildren to be Jewish. Smaller proportions say it would be very (22%) or somewhat (22%) important for their grandchildren to marry someone who is also Jewish.

The answers to these questions tend to vary by age, with older Jews generally assigning greater importance to Jewish continuity and in-marriage than younger Jews do. But, as previously noted in this report, there is also a kind of divergence taking place in the U.S. Jewish population, with a rising percentage of young Jewish adults who are Orthodox as well as a rising share who describe themselves – in terms of religion – as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular.

The question about future grandchildren captures one element of this divergence. Three-in-ten Jewish adults under the age of 30 (31%) say it would be “not at all” important for their future grandchildren to be Jewish, which is significantly higher than the share who say this in any other age group. At the same time, 32% of the youngest Jewish adults say it would be “very important” for their grandchildren to be Jewish, which is on par with the share who say the same among older age groups. Among the Orthodox, 91% say it is very important for their grandchildren to be Jewish, compared with 4% among Jews of no religion.

Retention

The survey estimates that roughly 8 million U.S. adults were raised Jewish or had a Jewish parent. Six-in-ten were raised Jewish by religion (58%), while 7% were raised as Jews of no religion; another 35% had at least one Jewish parent but say they were not raised exclusively Jewish (if at all), either by religion or aside from religion.

Overall, 68% of those who say they were raised Jewish or who had at least one Jewish parent now identify as Jewish, including 49% who are now Jewish by religion and 19% who are now Jews of no religion. That means that one-third of those raised Jewish or by Jewish parent(s) are not Jewish today, either because they identify with a religion other than Judaism (including 19% who consider themselves Christian) or because they do not currently identify as Jewish either by religion or aside from religion.

Among all respondents who indicate they have some kind of Jewish background, those who were raised Jewish by religion have the highest retention rate. Nine-in-ten U.S. adults who were raised Jewish by religion are still Jewish today, including 76% who remain Jewish by religion and 13% who are now categorized as Jews of no religion. By comparison, three-quarters of those raised as Jews of no religion are still Jewish today; roughly half are still Jews of no religion and about one-in-five are now Jewish by religion. Among those who had at least one Jewish parent but who say they were not raised exclusively Jewish (either by religion or aside from religion), far fewer are Jewish today (29%).

Among people who were raised with a Jewish background, the share who identify as Jewish today is similar across age groups. However, older adults who were raised Jewish or had at least one Jewish parent are more likely to identify as Jewish by religion, while larger shares of young adults say they are Jewish aside from religion. For instance, among those ages 50 and older with a Jewish background, 57% identify as Jewish by religion, compared with 37% among adults under 30.

The data also shows that people with two Jewish parents are more likely than those with just one Jewish parent to retain their Jewish identity into adulthood. However, among people who have just one Jewish parent, younger cohorts are more likely than those ages 50 and older to be Jewish as adults, suggesting that the share of intermarried Jewish parents who pass on their Jewish identity to their children may have increased over time. Or, put somewhat differently, the share of the offspring of intermarriages who choose to be Jewish in adulthood seems to be rising.

The vast majority of adults who were raised with a Jewish background and who now are married to a Jewish spouse identify as Jewish today (95%). By contrast, far fewer of those who have a non-Jewish spouse are Jewish today (56%). However, this does not necessarily mean that marrying a non-Jewish spouse pulls people away from their Jewish identity. The causal arrow could just as easily point in the other direction: People whose Jewish identity is relatively weak may consider it less important to marry a Jewish spouse.

The survey also makes it possible to examine the retention rate of various institutional branches or streams of Judaism in America. Orthodox and Reform Judaism exhibit the highest retention rates of the major streams; 67% of Americans raised as Orthodox Jews by religion continue to identify with Orthodoxy as adults. Similarly, most people raised as Reform Jews by religion also identify as Reform today (66%). The retention rate for those raised within Conservative Judaism is lower; four-in-ten people (41%) raised as Conservative Jews by religion continue to identify with Conservative Judaism as adults, although fully nine-in-ten (93%) are still Jewish.

In some ways, these patterns resemble the findings from the 2013 study. In both surveys, adults who no longer identify with their childhood stream tend to have moved in the direction of less traditional forms of Judaism rather than in the direction of more traditional streams. For example, roughly half of people raised within Conservative Judaism now identify with Reform Judaism (30%), don’t affiliate with any particular branch of Judaism (15%) or are no longer Jewish (7%), while just 2% of people raised as Conservative Jews now identify with Orthodox Judaism. Similarly, about one-quarter of people raised within Reform Judaism now either have no institutional affiliation (14%) or are no longer Jewish (12%), while just one-in-twenty now identify with Conservative Judaism (4%) or with Orthodox Judaism (1%).

However, the share of adults raised within Orthodox Judaism who continue to identify as Orthodox is higher in the new study (67%) than it was in the 2013 survey (48%). This may be due (at least in part) to the fact that, in the new study, the sample of adults who say they were raised as Orthodox Jews includes a larger percentage of people under the age of 30. The 2013 study indicated that the Orthodox retention rate had been much higher among people raised in Orthodox Judaism in recent decades than among those who came of age as Orthodox Jews in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. The new survey included too few interviews with those raised as Orthodox Jews to be able to subdivide them by year or decade of birth.

With thanks to the

+

Please find to read:

- Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah and the Birth of Judaism as We Know It

- A Secret of our Enemy :Inter-Ethnic Fault Lines Among the Jews (Full Article)

- As there is a lot of division in Christendom there is too in Judaism

- Surprise: Ashkenazi Jews Are Genetically European

- Where our life journey begins and inheritance of offices of parents

- Second core value of Conservative Judaism opposite use of native tongue in Reform Judaism

- An American Embassy to the Eternal Capital of the Jewish people, Jerusalem

- Possibility for a Jew to replace Donald Trump

- A Spot at the Kotel Won’t Save Us: A Crisis in American Judaism

- What about Faith is Our Choice?

- Judaism and Jewishness in 2020 America

- Jews for Jesus Valueing Jewish Identity

- Anti-Semitism in the United States

- American Judaism: Reform, Conservative, Orthodox and Reconstructionist

- American Conservative Judaism

- Jewish Americans in 2020

- Is it possible to have Jews for Jesus?

- Is it a Jewish or Christian Faith?

+++

Related

- Census Unearthed: Small Area Statistics

- First Comes Love, Then Comes Marriage

- What is Love

- Family, a Community of Life and Love

- Relationship Minute: Love Your Partner Better

- Relationship Minute: Update your Love Maps

- A Few Marriage Thoughts

- Arranged Marriage

- A cynical view on arranged marriage

- Church Culture In Keralite Churches In The US

- Race/ethnic intermarriage trends, 2008-2018

- Intermarriage seems a revolutionary knot

- Rav Avigdor Miller on When To Ignore Your Parents

- How mindful discussions lead to successful intermarriages

- Jewish Identity Part 2: Descent By One Parent?

- Beyond The Labels

- Rav Avigdor Miller on Preparing For Judgement Day

- Why can’t I be secular?

- Reality is Broken

- the ring pandemic

- 9 Things I Have Learned In 9 Years of Marriage

This article discusses how one parent of either sex is sufficient to make a child Jewish according to the Bible.

https://theslowroom.com/2021/07/13/jewish-identity-part-2-descent-by-one-parent/

LikeLike

Thank you very much for giving this link to a very interesting article going deeper into the matter of a pure Jewish bloodline, and writing:

and bringing some further arguments. Bringing yourself to the conclusion:

LikeLike